Project Citizen Shows Significant Impact on Teachers and Students

Posted in News | Tagged Project Citizen, Project Citizen Research Program

Georgetown University’s Civic Education Research Lab and the Center for Civic Education Host March Civic Engagement Conference to Discuss Findings

Washington, D.C. – The Project Citizen Research Program (PCRP), led by CERL Director and Georgetown University Professor Dr. Diana Owen, found that participants in the Project Citizen teacher professional development and curriculum improved significantly in the areas of civic knowledge, disposition, skills, and engagement as well as civic-related SEL competencies and STEM skills. Results were compared to those of participants in concurring traditional civics programs. Read the final PCRP report. More than 100 civic educators, researchers, and policymakers from across the country attended the Educating Students for Civic Engagement conference at Georgetown University on March 13-14 to discuss the impact of the Center for Civic Education’s Project Citizen on teachers and students.

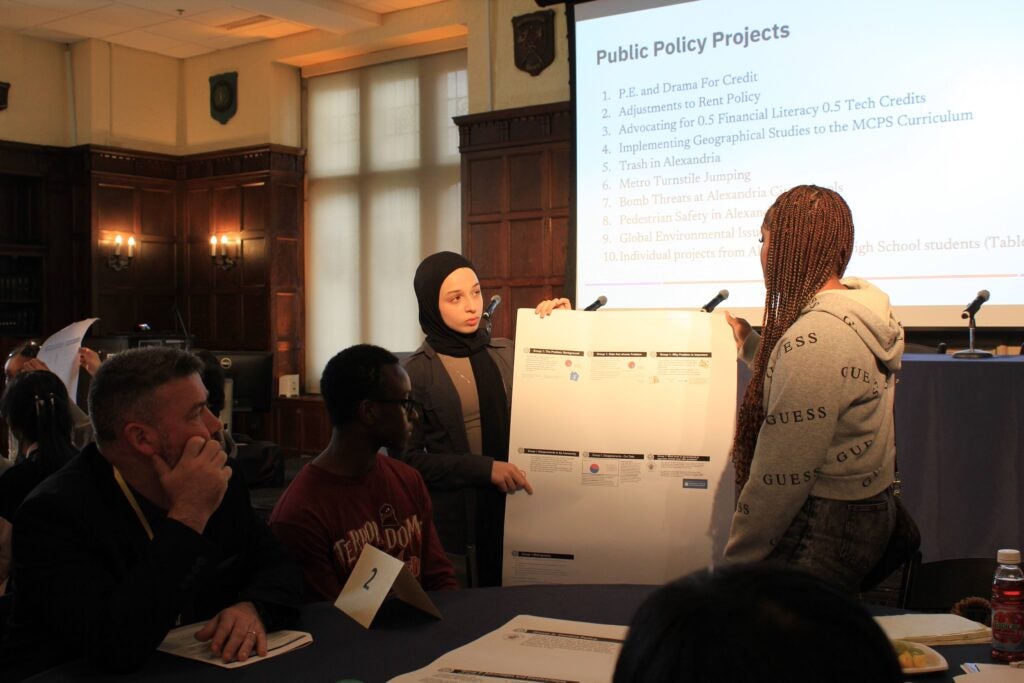

Presentations by prominent educators and scholars, panels, and roundtables discussed the implications of the PCRP findings for furthering democratic civic engagement, best practices in research and implementation of K-12 civic education programs, innovative civic engagement practices, next steps and new directions in civics research, and broader implementation of Project Citizen. Project Citizen students from Alexandria City Public Schools in Virginia and Northwest High School in Germantown, Maryland presented and discussed their civic engagement projects with conference participants during lunch on March 13.

PCRP followed 180 schools, 196 teachers, 2,590 middle school students, and 2,785 high school students over the course of three academic years from 2020-23. Of note, the first two years of the study, during the COVID pandemic, included virtual learning. Students worked as a class to research and develop proposals for solving a policy problem in their school or community which they presented to stakeholders. PCRP was funded by a grant from the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

To read more about the conference, including presentation slides and videos, visit the Center for Civic Education PCRP conference page. Below summarizes the findings for each of the Project Citizen research focus areas. Click on the title of each focus area for downloadable PDFs with charts.

Middle and high school students who were taught the Center for Civic Education’s Project Citizen curriculum had significant gains in their knowledge about American democracy, the U.S. Constitution, government institutions, and the public policy process. The civic knowledge scores of Project Citizen middle school students improved by 44% in year 1, 76% in year 2, and 66% in year 3 of the study. The civic knowledge scores of high school students increased by 27% in year 1, 56% in year 2, and 32% in year 3 of the study. Civic knowledge gains were significantly greater for middle and high school Project Citizen students than students who took a traditional civics class.

Teachers who took part in the Center for Civic Education’s Project Citizen professional development program reported that their participation greatly advanced their civic content knowledge. The program gave teachers the opportunity to learn from scholars and mentor teachers with expertise in American government and the policy process. Teachers had access to materials, resources, and webinars to supplement and enhance their civic content knowledge. Project Citizen teachers’ knowledge of American democracy, the U.S. Constitution, government institutions, and the public policy process increased by 8% in year 1, 15% in year 2, and 21% in year 3. Project Citizen teachers’ civic knowledge significantly exceeded that of teachers instructing traditional civics classes who had not received the Center’s professional development program.

Middle and high school students gained a greater sense of civic responsibility related to keeping informed about government and politics, paying attention to issues, and engaging actively in their community after participating in Project Citizen.

High school Project Citizen students’ scores on a civic responsibility index increased by 4% in year 1, 11% in year 2, and 17% in year 3. These gains were greater than for students in the control group.

Students became more interested in pursuing a career in government and possibly running for office one day after their experience with Project Citizen. The findings were more pronounced for high school students for whom government service is a more proximate option than for middle school students. High school Project Citizen students’ interest in future government service increased by 8% in cohort 1, 20% in cohort 2, and 24% in cohort 3. The rise in interest in government service was greater for the Project Citizen students than for those in the control group.

Civic dispositions are public and private traits, attitudes, and “habits of the heart” that are consistent with the common good and central to the functioning of a healthy democracy. While teachers desire to have their students become good global citizens, civic dispositions typically are given little attention in the classroom. The Project Citizen teacher professional development program focused on the development of students’ civic dispositions through classroom instruction. After participating in the PCRP, teachers were more inclined to highlight civic dispositions in their lessons. The percentage of Project Citizen teachers who emphasized developing dispositions to become involved in community affairs a great deal increased over the course of the study from 21% to 46% in year 1, from 21% to 58% in year 2, and from 17% to 32% in year 3. Control group teachers placed limited emphasis on civic dispositions on the pretest and posttest for all study cohorts.

Project Citizen students felt more prepared to participate in their communities and public life after taking part in the program. They had a better understanding of policy issues facing the country, they felt able to work on solving a problem in their community, and they could identify the official or branch of government to contact about a community problem. Middle school Project Citizen students’ civic skills increased by 8% in Year 1, 13% in Year 2, and 6% in Year 3. There were no significant differences in control group students’ civic skills from pretest to posttest. High school Project Citizen students’ civic skills increased by 7% in Year 1, 10% in Year 2, and 9% in Year 3. The increases were greater than for the control group.

Project Citizen teachers were much more likely to emphasize the skills needed for democratic engagement in their classes after the professional development program. The number of teachers who focused a great deal on civic skills increased from 40% to 73% in Year 1, from 57% to 71% in Year 2, and from 22% to 47% in Year 3. Control group teachers did not place as much emphasis on civic skills.

Project Citizen teachers were much more likely to integrate activities that convey civic skills into the lessons. These skills include having students work actively in their school or community to solve a problem, develop an action plan for dealing with an issue, contact public officials, and post information about a community issue on social media or a blog. Teachers’ integration of activities that convey civic skills into their lessons increased by 156% in Year 1, 136% in Year 2, and 99% in Year 3. Teachers in the control group were less likely to use civic activities in their classrooms during the study period.

Civic Engagement (Duty to Vote)

Middle and high school students had a strong sense of their duty to vote at the outset of the study. Project Citizen students’ sense of their responsibility to exercise their right to vote in an election increased significantly after receiving the curriculum. The percentage of middle school students who considered voting a “top priority” rose from 28% to 39% in year 1 of Project Citizen and 36% in years 2 and 3. High school students’ commitment to voting as a “top priority” increased from 45% to 52% in year 1, and from 37% to 39% in years 2 and 3. The percentage of high school students who did not consider voting to be much of a responsibility declined from 20% to 16% in cohort 1, from 28% to 21% in cohort 2, and from 29% to 22% in cohort 3. Middle and high school students in the control group’s sense of their voting duty remained stable after a traditional civics class.

After participating in Project Citizen, middle and high school students were more likely to indicate that they would turn out to vote in elections if they had the opportunity. The percentage of middle school Project Citizen students responding that they would be very likely to vote rose from 56% to 63% in year 1, from 50% to 53% in year 2, and from 44% to 52% in year 3. For high school Project Citizen students, the likelihood of voting increased from 69% to 72% in year 1, from 63% to 69% in year 2, and from 66% to 76% in year 3 of the study. Middle and high school students in the control group were less likely to turn out to vote given the opportunity than the Project Citizen students.

Project Citizen teachers became more confident in their ability to get their students to engage civically after participating in the professional development program. The percentage of Project Citizen teachers who felt very effective in encouraging their students to engage in elections increased from 51% to 70% in cohort 1, from 55% to 71% in cohort 2, and from 47% to 54% in cohort 3. Control group teachers’ effectiveness in encouraging students to engage in elections increased slightly or declined over the study period.

Project Citizen students gained civics-related SEL skills during the program. They felt better able to solve problems, work collaboratively, and express their views. Middle and high school students’ ability to express their views in front of others, contact local news outlets and government officials, and use social media to publicize a community problem increased significantly after Project Citizen. Middle school students’ scores on an index of civic expression skills increased by 9% in Year 1, 11% in Year 2, and 13% in Year 3. High school students’ scores improved by 7% in Year 1, 8% in Year 2, and 8% in Year 3.

77% of teachers felt that Project Citizen contributed to their students’ acquisition of SEL competencies. Teachers gained a greater sense of self-efficacy from their participation in Project Citizen. Their perceptions of their ability to convey civic knowledge, promote student self-care and self-management, develop students’ relationship skills, promote respectful classroom discourse, encourage student civic engagement, and provide educational resources to others improved significantly. Teachers’ self-efficacy improved by 15% in Year 1, 9% in Year 2, and 7% in Year 3. Control teachers’ sense of their ability to convey SEL competencies to students declined in each academic year.

Project Citizen students were encouraged to use science, technology, and math skills when researching a problem in their community/school and developing policy solutions. Students were able to make the connection between STEM and their civics classes after participating in Project Citizen. The effects were not apparent for control group students. Students’ use of science, technology, and math skills was measured on an index before and after their Project Citizen or traditional civics class. The difference in middle school students’ belief that they could use STEM skills to address community problems improved by 7% in Year 1 and 6% in Years 2 and 3. High school students’ STEM index scores increased by 8% in Year 1, 9% in Year 2, and 6% in Year 3.

Project Citizen teachers were more inclined to have their students use STEM skills after the professional development program. The percentage of Project Citizen teachers who had students use STEM skills doubled from 25% on the pretest to 50% on the posttest. There was no change for the control group. 42% of Project Citizen teachers indicated that they were very prepared to incorporate STEM into the civics curriculum after participating in PCRP compared to 3% pre-program.